Our Diverse Heritage: Marion’s Black History Part 10

Celebrating Black History Month in Marion County

February 13, 2024

Part 10: Dunbar High School

Earlier we discussed the origins of the Black School in Marion County when Alfred Meade and other black community leaders (Bossy Lewis, Link Jones, John Jackson, Peter Fagan, Tansy Hill and Benjamin Jackson) borrowed money to buy a lot for a school in 1868. When WV achieved statehood, education of black children at public expense was delayed. In the report of William Ryland White, a Fairmont native and first State Superintendent of Public Schools in 1864, he noted that the Negroes had been too long and too mercilessly deprived of this privilege. “I regret to report that there are not schools for the children of this portion of our citizens; as the law stands I fear they will be compelled to remain in ignorance.” By 1866, therefore, the legislature enacted a law providing for the establishing of public schools for Negroes between the ages of six and twenty-one years, but again funding was always in question. Meade, with the backing of local businessmen and Francis Pierpont, obtained a loan and built the school.

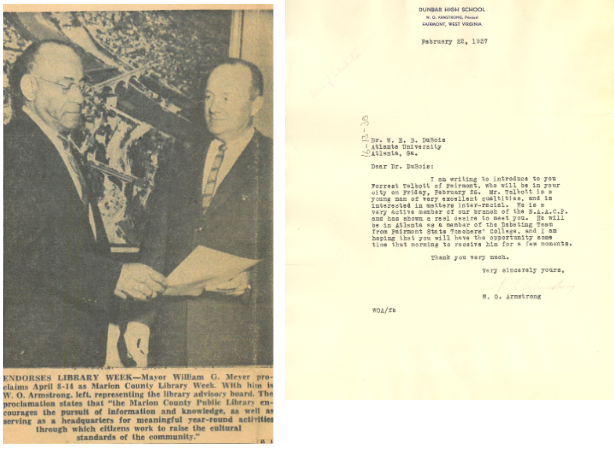

While the original frame building was replaced in 1901, a new facility was planned as part of a major city-wide building program. Eventually the school was named “Dunbar” in honor of Paul Laurence Dunbar, a successful black writer whose works on education symbolized opportunity to the African American community. The faculty were highly qualified. Dr. W. O. Armstrong joined the faculty around 1910 and served for more than 45 years as principal of Dunbar School.

Dr. Armstrong was probably the first local principal who obtained with a terminal degree. He journeyed to W.Va. from New Haven, Connecticut, to attend W.Va. State College Armstrong. Later he was the first African American admitted to West Virginia University. After the close of Dunbar, Dr. Armstrong was the assistant principal of Miller School.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated schools were unconstitutional. This landmark ruling overturned an earlier case, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), in which the court had declared that ‘‘separate but equal’’ facilities did not violate the 14th Amendment.

Following this ruling, Governor William C. Marland pledged to obey the edict and foresaw no serious difficulty in integrating West Virginia schools. State Negro Schools Supervisor J. W. Robinson expressed agreement with the ruling, believing that the decision would increase opportunities for Black teachers. At the time of the decision there were 420,000 White and 26,000 African-American students attending school in West Virginia.

The era of the all-black Dunbar School ended. Not all the teachers found employment but a number of them were able to continue in education. A look at some of those teachers follows.